“For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move.” – Robert Louis Stevenson

Hong Kong. The cultural, commercial, banking, shipping, fashion, architecture and vice center of Asia, the Orient’s answer to New York City. Under British rule from 1842 until 1997, then returned to China under a century-old agreement, it retains a British flavor here and there, while the population remains more than 90% Chinese. For me it’s a complete change from the last six weeks: I encounter blonde hair, blue eyes, and British-accented English here every day.

When the Chinese regained possession of Hong Kong in 1997 they surprised many observers by creating an Autonomous Region scarcely distinguishable from a sovereign country. Hong Kong issues passports, controls immigration, and has retained its own currency (the Hong Kong $, one of the most traded currencies in the world). Very little tax revenue goes to Beijing, and the tiny Chinese Army contingent is confined to their tiny base. The local joke is that nothing changed but the postal codes.

Bicycling in Manhattan and a handful of the world’s largest cities didn’t really prepare me for Hong Kong. For one thing, nobody else bicycles. The spaces between the huge, two-story busses and trolleys (I’ve lived in smaller houses) are filled with shirtless men straining to push loaded carts of goods, trucks loading and unloading, shops with wares spilling out onto the street, and always relentless throngs (real throngs!) of pedestrians flooding each intersection, crowding the bus stops, and pouring like a river down the sidewalks, bumping shoulders and squeezing through somehow. It’s hilly, even mountainous, and many streets are elevated, winding through the skyscrapers like a life-sized video game. They drive on the left here, and it takes a surprising amount of concentration to stay oriented and look in the proper direction for traffic and danger.

This describes “downtown”, which is vast and separated into mainland and island areas, linked by futuristic bridges. Dozens of ferries and hundreds of other craft make a lively, chaotic waterfront scene. Helicopters ferry people around and through the skyscrapers, landing atop the largest. I was told that some bankers and CEOs commute by helicopter daily, and rarely set foot below the hundredth floor. I have seen more Ferraris, Maseratis and Lamborghinis here than in all the other places combined.

But the magic bicycle brings me to the abrupt edge of downtown, and suddenly I am gliding through park-like boulevards past gated mansions, and into huge parks; a palm-treed tropical paradise. Actually, gliding is not the best term to describe the riding in this steep terrain. Sweating and zooming is more like it. Sweating because I am as far south as Cuba, and the weather is like Vermont in midsummer. Palm trees, banana plants, and unfamiliar flora and fauna catch my eye and slow me down. So do the expansive coastal mountain vistas, hazy in the humid warmth. I am liking this place.

My route to Hong Kong brought me through China’s agricultural heartland. A few posts back I described my plan to take a train to mountainous Yunan Province, then another to historic, scenic Guilin, before cycling to Hong Kong.

Instead, I mapped out a route from city to city, more or less directly south from Xian. One reason was because I had great, varied riding between (mostly) nice, clean and interesting cities, and I had little motivation to seek an improvement. Secondly, my train ride to Xian, while fun, did not make me eager to repeat the experience. And even though I have confessed to being a lazy tourist, passing by the usual attractions, I managed to accidentally visit Mao Zedong’s boyhood home, and the birthplace of the of the paper making process, and some pretty nice natural areas: waterfalls and hot springs bamboo forests.

I followed the main provincial highways through terrain that became increasingly hilly and mountainous toward the south. The agriculture and industry was varied, and tended to concentrate in regions. Harvest season seemed to be in full swing everywhere as I traveled from temperate to tropical zones. Crops were being loaded into trucks, and roadside stands were everywhere, often offering a single product like grapes or kiwis. I tried a new citrus fruit, new to me anyway, the pomelo, like an oversized grapefruit with an inch-thick skin, juicy and tart. The list of crops I saw is long. Very little of the culture and harvest was mechanized. Rarely was the landscape without hoeing or harvesting farmers. Many were women, who surprised me by dressing for field work in clean stylish clothing, except for rubber mud boots.

Southward, through the countryside, through city after city, I cycled for weeks. The road was mostly good, occasionally a muddy mess. Once every week or so when the opportunity arose, I left the main highway and chose some back roads, navigating by compass rather than turn-by-turn. One of these rides brought me deep into a mountain valley where a tiny, rutted and rocky dirt road carried little traffic, no trucks or cars but many pedestrians and motorcycles. Bicycles were rare, too, because the terrain was up and down and the road rough. Back there the terraced rice paddies were busy with the harvest, and villages with their 500-meter stretch of concrete roadway were bustling with trade, kids, elders, and life in general. I had to wonder what it was like living there, hours of difficult travel from the nearest highway, hours more to the nearest city. I got a taste of it when I ran out of daylight while still miles from a hotel. Sign language, my phone’s translator, and a very enthusiastic citizen helped me find a “guest house” in a tiny village of perhaps 500 people. A nice extended family in a small village home kept a room for visitors; they had a bountiful garden, chickens, and a pig out back, and their front doorstep was right on the street. Dinner was great; greens cooked with bacon, rice, eggs, dumplings. But I was a bit disappointed to find that my room was reached by passing through the room where grandma and teenage daughter slept, and lacked screens on the window. The straw mattress housed fleas, and I was never sure if the half-bucket of water was my toilet or not. Battling mosquitoes and fleas, I didn’t sleep well. Still, I felt compelled to leave more than the $3 or so that was requested. I skipped breakfast and was on the road early.

I fell into a routine, bicycling through the countryside during the day and staying in a city hotel at night. Up at 7:00, breakfast was included at most hotels. Packing and checking out put me on the street at 9:00. My needs before leaving the city included buying drinking water, fruit and baked goods for the day’s ride. Fancy downtown bakeries had the best baked goods, but I was often fooled by the products. What looked like a fruit pastry might contain seafood; what looked like a grilled-cheese sandwich tasted like cheesecake; a roll or bun could contain anything. Bananas, citrus fruit, plums and grapes would be purchased on the street without dismounting. My other need was wi-fi for e-mail and the day’s map and route calculations. (The hotels rarely had wi-fi, but often had computers in the room with fast internet connections.) I would find wi-fi reliably at large cell-phone stores, especially Apple iPhone dealers. They would give me the password and a seat, and bring tea. Sometimes I would just walk down the street and find, among the password-protected ones, unlocked wi-fi from a mystery source. Once hooked up I would punch in my target city (decided the night before in the hotel computer, aiming for something at least 45 miles away but less than 80, preferably less than 70). Then I would set off knowing what kind of day I had ahead. Earlier in the year I was stopping often for rest and snacks. Now I ride until I find a lunch spot, either picnic or restaurant, trying to pass the half way mark before stopping. After lunch I would ride to my target city in one go, pushing hard in the afternoon. Arriving in the new city I slow my pace and look around, finding the city center before checking out a couple of hotels. I aim for the middle-grade hotels at $25 of $30; the best are twice as much money, and the cheaper ones, $15 or $20, are not clean enough for comfort.

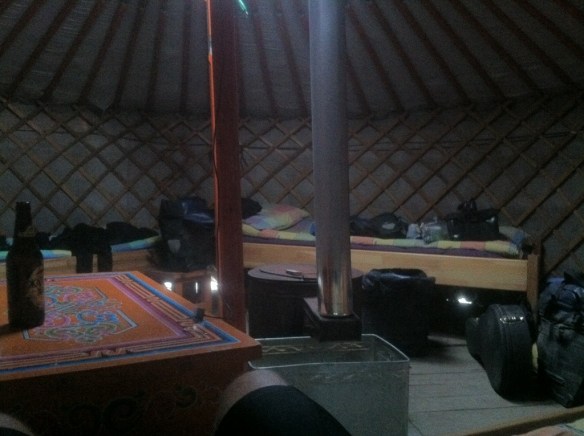

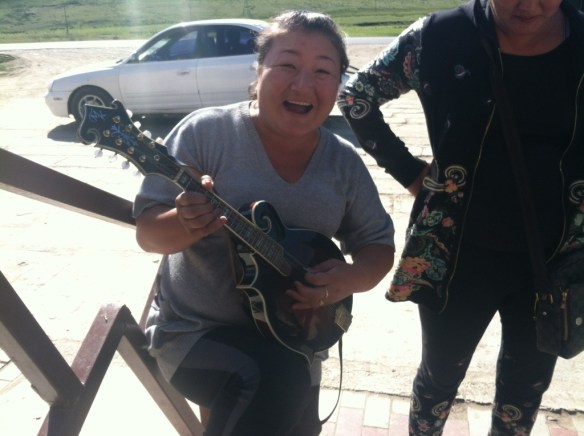

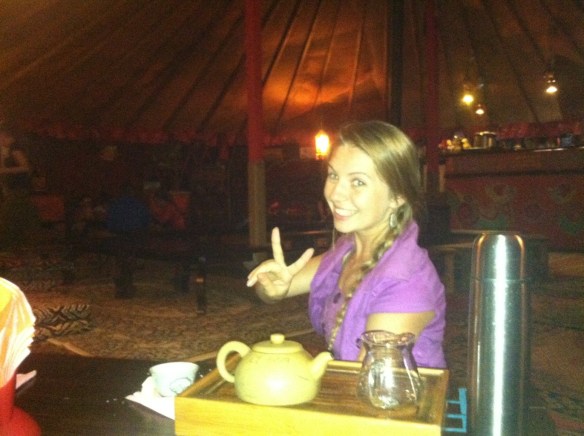

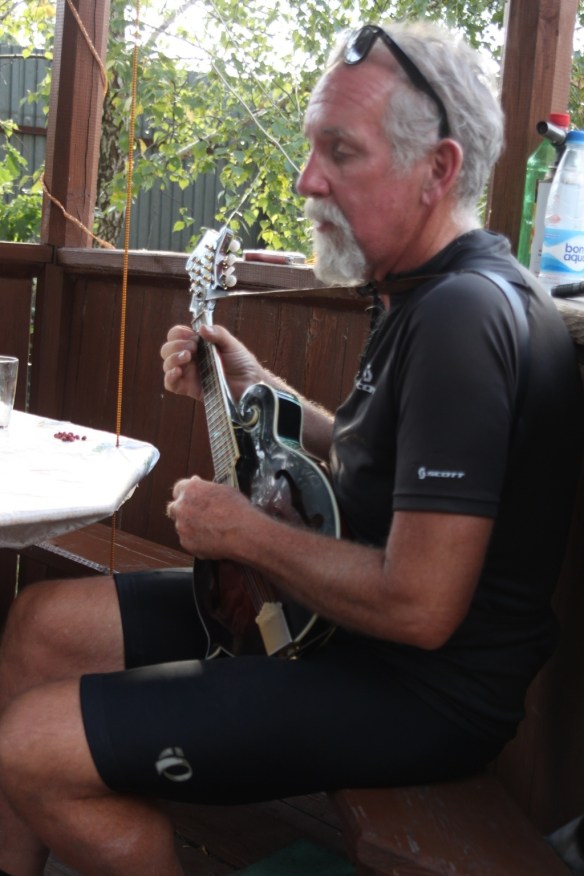

After checking in I wheel my bike to the elevator. (If I ask about the bike, I am often directed to store it downstairs, but I find it really convenient to bring it to the room. Half the time the staff objects but the manager lets me go. In the final weeks I had much rain and mud, and cleaned my bike in the room, taking care not to leave a mess.) After showering I rinse out my clothes in the sink and hang them to dry. Then I head down to the street and find dinner (unless lunch was in a restaurant), walk around the neighborhood, and return to my room with a couple of bottles of beer. There I read, use the computer, and eat the fruit and baked goods if I skipped dinner. I play mandolin for a while, and then read my books, my New Yorker and Atlantic magazines, either on my phone or on the hotel computer. By 10:00 or 11:00 I am asleep. If this account of life on the road sounds boring, I can assure you that it isn’t. The riding is interesting and fun, and the evenings are relaxing and pleasant. The contrast with my recent experiences in Siberia and Mongolia is extreme; those places were an extreme contrast with Eastern Europe, Europe, etc. I feel lucky to enjoy all this variety of experience, with only a simple bicycle and some things I packed way back in January, way back in Vermont.

As I approached Hong Kong I crossed the huge, dense Guangzhou-Dongguan-Shenzhen urban area. My final day was through completely congested city traffic, mostly on a six-lane superhighway. With a stiff tailwind and a generally downhill ride to the sea, it was a fast, wild ride. I was pumped up. The Pacific Ocean came into view, and I burst out laughing! I boarded a fast hydrofoil passenger ferry and an hour later I was in Hong Kong, grinning like a fool. It was a rather challenging three hours of navigation to find David, the Couch Surfing host I had arranged a week earlier. When I parked my bike in his living room, it was a moment, and the whole trip ran through my mind, fast-forward style, instant replay. Whew!

David is a quiet and somewhat shy librarian from Utah with a Mormon upbringing; we are not exactly similar personalities. He quickly made me feel at home in his elegant high-rise apartment overlooking the busy harbor. He’s a musical person who just acquired a mandolin, and we enjoyed some jigs and reels with his friend How, a young concert violinist with incredible skill. By the next day David and I had, in spite of our seeming dissimilarities, shared our stories and found that we understood each other. I have to say that I was soon very fond of him. We are kindred spirits after all.

After dinner one evening we went for a walk. David surprised me by climbing a fence, scrambling over rocks and bringing me down to a tree-shrouded section of shoreline. Scrambling behind him in my clunky bike shoes, I was the slow one. He shared a lot of Hong Kong history with me, and knew about the flowers and trees growing nearby. (Did you know mangoes have males and females, and grow in pairs, husband and wife?) When he threw off his t-shirt and jumped in the harbor for a swim, and I declined, I had to wonder who was the wild one and who was the mild one. Without much fuss, David threw a little music party for me, with some good local musicians, a banjo player and mandolinist. David’s wonderful housekeeper Maria made it a feast as well.

Early in the trip some members of the Hong Kong Bicycle Alliance, a club and advocacy group, made contact with me and offered to help me when I came to Hong Kong. I’ve been in touch and Martin, the main man, is getting a bicycle box for me and preparing to help me get to the airport. I will stay with David for another day or two, then stay with Martin on the other side of town. I scheduled more than a week here, thinking I might buy a tailored suit of clothes, legendarily cheap here, and enjoy some night life. But the road and the money ran out at about the same moment. Maybe next time.

I’m spending part of my time here reading about the storm in New York. Some of my good friends were quite affected by the storm, and I have been checking Facebook frequently, getting up-to-the minute reports from Greenwich Village. Also, I bought some inexpensive clothing to wear on the plane, and I am relaxing in jeans and a t-shirt, and real shoes, for the first time in ten months. And, about once every half hour, I break into a goofy grin and think,”Woo! I did it!”

My flight is on November 9. On November 11, Sunday evening, I will be at the Tavern on Jane Street dispensing stories, hugs and souvineers. I hope to see you there. And of course, I’ll be back on Jane Street a week or so later for my 26th Christmas tree season. After Christmas I’ll sleep for a week and then look back on a significant year. But only for a minute. I’m looking toward the future mostly, and it looks great. So many choices, all of them appealing! My plans include more travel, more music, more outdoor life. I have a craving for a tiny little home, a fire in the hearth, a garden. It could be anywhere, but I likely won’t settle very far from my grandchildren and my friends.

I want to thank you sincerely for reading. It’s wordy, the pictures are lame, and it’s only a bike ride, but more than 200 of you have read every post. I really try hard to evoke the feelings and describe the experiences vividly and honestly, and it has been a privilege to share it with you. I like blogging so much that I plan to put these “London to Hong Kong” pages off to the side and start blogging on other topics: music, bicycles, my world view, politics, philosophy and other nonsense. Check in now and then. Double thanks to all those people who eased my path and shared their lives for a brief moment. I will never forget your kindness and love. Dear readers, my love goes out to you. Spread it around.